Whipple Procedure for Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia of the Pancreas

Main Text

Table of Contents

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) is an uncommon autosomal dominant inherited condition with an estimated frequency of 1:30,000 across the general population. 35% –75% of patients with MEN-1 ultimately develop neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas, which present the most significant threat to long-term survival. Pancreatectomy remains the only curative therapy for such patients and has become increasingly safe over the past few decades. Here we present the case of a young woman with MEN-1 who was found to have a 3.5 cm well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor in the head of the pancreas. We outline the natural history, preoperative care, intraoperative technique, and postoperative considerations.

MEN-1 syndrome is an autosomal dominant inherited syndrome related to inactivating mutations in the tumor-suppressor protein menin. Unfortunately, MEN-1 syndrome occurs in the general population with an estimated frequency of 1:30,000, and 35%-75% of people with the condition develop neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas.

Our patient is a 26 year-old female with a known history of MEN-1 in immediate family members. She had been in great health until development of headache and lactation without any abdominal pain or discomfort, weight loss, or symptoms of hypoglycemia. Work-up revealed a pituitary adenoma which was ultimately treated with cabergoline with a resolution of symptoms. Subsequent work-up for additional MEN-1 related tumors included an MRI and CT studies that revealed a 3.5 cm mass in the head of the pancreas. Our patient then presented for surgical evaluation of pancreatic head neuroendocrine tumor.

She has no prior medical or abdominal surgical history. Her only medication at time of presentation is cabergoline, and she only drinks an occasional glass of wine. Her family history is notable for MEN-1; her maternal grandmother had a pancreatic tumor and underwent Whipple procedure at age 50. Her father and two uncles have pancreatic and parathyroid tumors.

Physical exam revealed a healthy-appearing young lady with a pulse of 80 bpm and blood pressure of 110/80 mmHg. She has no scleral icterus, and neither cervical, nor supraclavicular lymphadenopathy. She has no palpable masses in the thyroid. Her lungs are clear to auscultation bilaterally, and her heart has regular rate and rhythm without murmur. Her abdomen is soft, non-tender, nondistended, and without any palpable masses, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, or ascites. Skin and extremities exams are also without any focal abnormalities.

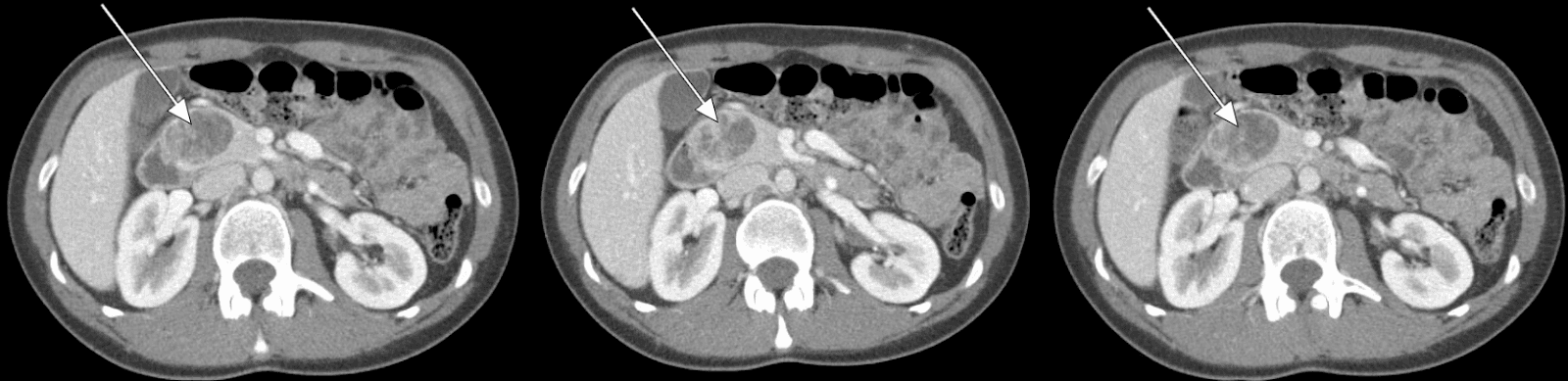

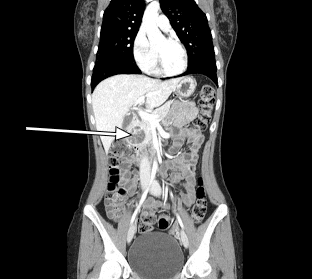

Our patient underwent an abdominal CT scan with arterial-phase contrast that showed a 3.5 cm enhancing lesion in the head of the pancreas (Figures 1, 2). Subsequent EUS with biopsy confirmed a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor. Additional pathology evaluation found tumor cells to be positive for chromogranin and CD56 but with a low Ki-67 index of 3%-4%, suggesting a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor.

Patients often present to their surgeon having already undergone an array of radiologic studies. The most important imaging modality is a three-phase abdominal CT scan: without contrast, with arterial-phase contrast, and with portal-venous phase contrast. Abdominal MRI can also provide useful information to differentiate between tumors of unclear etiology. However, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) have very characteristic features on CT scans that, coupled with a patient’s history and physical, can often provide adequate information for surgical recommendations.1,2

PNETs are typically isodense with pancreatic parenchyma visible on pre-contrast images. However, the tumors have marked enhancement on arterial phase imaging with a minority of tumors also being evident on portal venous phase. On rare occasions, PNETS can be either hypovascular or cystic in nature, which diminishes one’s ability to discriminate between other lesions by CT alone. Endoscopic ultrasound with biopsy is being increasingly used to localize particularly small lesions. Though highly sensitive for smaller lesions, EUS is also highly operator-dependent.

Figure 1. Abdominal CT Scan Abdominal CT revealing a 3.5-cm enhancing lesion associated with the head of the pancreas.

Figure 2. Sagittal CT Scan Sagittal CT revealing a 3.5-cm enhancing lesion associated with the head of the pancreas.

The clinical manifestations of MEN-1 syndrome include parathyroid and pituitary adenomas as well as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs). Although PNET’s account for less than 3% of all pancreatic neoplasms in the general population, 30%–80% of patients with MEN-1 will develop evidence of a neuroendocrine tumor.3-5 Approximately half of all deaths in patients with MEN-1 can be attributed to malignant endocrine neoplasms.

Patients with lesions in the head of the pancreas will most likely require a pancreaticoduodenectomy to obtain adequate oncologic resection. Variations in reconstruction include pylorus preservation, antecolic vs retrocolic duodenojejunostomy (or gastrojejunostomy), and method of pancreaticojejunostomy. However, these variations have resulted in little differences in immediate and long-term outcomes.6-8 Lesions in the body or tail of pancreas can undergo a middle or distal pancreatectomy, respectively. Regardless of the procedure performed, regular surveillance with axial imaging is required given ongoing risk of developing additional PNET in remaining pancreas.

Given that the patient has a nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor at the head of the pancreas, the Whipple procedure is the only potential curative option. We chose to conduct a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy because no difference in outcomes has been observed in its variations.6,7

Here we present the case of a 26 year-old female with MEN-1 and a nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor at the head of the pancreas. She underwent an uncomplicated pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy and has recovered without any additional complications. Final pathology revealed a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor with 0 of 12 lymph nodes positive for malignancy.

Barring any intraoperative complications or specific patient comorbidities, most patients should be extubated in the operating room. We typically leave a nasogastric tube overnight and remove on postoperative day number 1. Blake drains should be monitored for volume, character, and amylase content.9 Multiple algorithms have been developed to determine optimal timing of drain removal. Ultimately, drains can be removed if drainage is low volume, with low-amylase levels (< 600 U/L), and is non-suspicious in character. However, should drain output remain high-volume or have high concentration of amylase, drain(s) should remain in place. Additionally, surgeons should have a low-threshold to reimage patients after surgery should they show signs of uncontrolled pancreatic leak including tachycardia, fever, abdominal pain, or unexplained leukocytosis.

The pancreatic stent should remain in place until three weeks postoperatively at which point it can be removed in clinic. Patient diet should be slowly advanced as tolerated, with care to monitor for delayed gastric emptying.

In the absence of explicit complications, we usually provide routine restrictions after laparotomy including avoiding heavy lifting for four to six weeks after surgery. Patients usually return to clinic for follow-up either two or three weeks after surgery (depending on whether a pancreatic stent was used). One recent study followed sixteen patients with MEN-1 after pancreatectomy for non-functioning neuroendocrine tumors.10 10 of these patients developed new PNETs after a median follow-up of 74 months. Regardless of the specific procedure performed, patients should therefore follow-up with routine axial imaging to evaluate for recurrent or metastatic disease.

The Whipple procedure remains the only option for curative treatment of pancreatic head malignancies, including neuroendocrine tumors. Mortality from the procedure has improved markedly over the past few decades; perioperative death rates are now < 2% at high-volume centers.11 However, morbidity rates upwards of 40% continue to plague the surgery. Pancreatic fistulas occur in approximately 10-15% of cases. Recent work suggests that external pancreatic duct stents can help reduce clinically significant fistula in high-risk patients (those with a soft gland and small pancreatic duct).12 Although there has been considerable debate about the role of closed-suction drainage after the Whipple procedure, a recent randomized controlled trial showed that routine drainage also reduces the frequency and severity of postoperative complications. Multiple studies are underway to identify strategies to reduce the frequency of surgical site infections that presently occur in 8%–10% of these procedures. Increasing data suggest that the standard preoperative prophylactic antibiotics may not be adequately covering biliary flora, which is frequently present after preoperative instrumentation of biliary tract (ERCP, sphincterotomies, stents, etc.).13 Preliminary reports suggest that surgeons might consider tailoring antibiotic choices to microorganisms most frequently seen in their respective populations. Delayed gastric emptying also occurs in 25%–30% of patients following pancreaticoduodenectomy with no clear association between pylorus-preservation vs classical Whipple or antecolic vs retrocolic duodenojejunostomy (or gastrojejunostomy).14

Editorial Update 06/24/2018: The patient is now nearly 4 years post-surgery with no evidence of recurrent disease in her pancreas, although she did require removal of a parathyroid adenoma.

Special pieces of equipment used in this procedure include a Bookwalter retractor, a pediatric feeding tube (3-5 French), dilators, and an argon beam coagulator (optional).

None.

Consent for the use of clinical history, radiology, and intraoperative video was obtained from the patient and providers involved in compilation of this case report and filming.

References

- Philips S, Shah SN, Vikram R, Verma S, Shanbhogue AKP, Prasad SR. Pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: a current update on genetics and imaging. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(1014):682-696. doi:10.1259/bjr/85014761.

- Lewis MA, Thompson GB, Young WF Jr. Preoperative assessment of the pancreas in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. World J Surg. 2012;36(6):1375-1381. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1539-7.

- Hausman MS Jr, Thompson NW, Gauger PG, Doherty GM. The surgical management of MEN-1 pancreatoduodenal neuroendocrine disease. Surgery. 2004;136(6):1205-1211. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2004.06.049.

- Tonelli F, Fratini G, Nesi G, et al. Pancreatectomy in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1-related gastrinomas and pancreatic endocrine neoplasias. Ann Surg. 2006;244(1):61-70. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000218073.77254.62.

- Lairmore TC, Chen VY, DeBenedetti MK, Gillanders WE, Norton JA, Doherty GM. Duodenopancreatic resections in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Ann Surg. 2000;231(6):909-918. doi:10.1097%2F00000658-200006000-00016.

- Diener MK, Knaebel HP, Heukaufer C, Antes G, Büchler MW, Seiler CM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of pylorus-preserving versus classical pancreaticoduodenectomy for surgical treatment of periampullary and pancreatic carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;245(2):187-200. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000242711.74502.a9.

- Tran KTC, Smeenk HG, van Eijck CHJ, et al. Pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy versus standard Whipple procedure: a prospective, randomized, multicenter analysis of 170 patients with pancreatic and periampullary tumors. Ann Surg. 2004;240(5):738-745. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000143248.71964.29.

- Eshuis WJ, van Eijck CHJ, Gerhards MF, et al. Antecolic versus retrocolic route of the gastroenteric anastomosis after pancreatoduodenectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2014;259(1):45-51. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a6f529.

- Van Buren G II, Bloomston M, Hughes SJ, et al. A randomized prospective multicenter trial of pancreaticoduodenectomy with and without routine intraperitoneal drainage. Ann Surg. 2014;259(4):605-612. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000460.

- Lopez CL, Waldmann J, Fendrich V, Langer P, Kann PH, Bartsch DK. Long-term results of surgery for pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms in patients with MEN1. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396(8):1187-1196. doi:10.1007/s00423-011-0828-1.

- Fernández-del Castillo C, Morales-Oyarvide V, McGrath D, et al. Evolution of the Whipple procedure at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Surgery. 2012;152(3)(suppl 1):S56-S63. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.022.

- Pessaux P, Sauvanet A, Mariette C, et al. External pancreatic duct stent decreases pancreatic fistula rate after pancreaticoduodenectomy: prospective multicenter randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2011;253(5):879-885. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e31821219af.

- Donald GW, Dharma S, Lu X, et al. Perioperative antibiotics for surgical site infection in pancreaticoduodenectomy: does the SCIP-approved regimen provide adequate coverage? Surgery. 2013;154(2):190-196. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2013.04.001.

- Kawai M, Tani M, Hirono S, et al. Pylorus ring resection reduces delayed gastric emptying in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial of pylorus-resecting versus pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2011;253(3):495-501. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e31820d98f1.

Cite this article

Lillemoe K, Loehrer A. Whipple procedure for multiple endocrine neoplasia of the pancreas. J Med Insight. 2018;2018(16). doi:10.24296/jomi/16.